Some of my roots go to Laurel, Mississippi. My maternal great-grandparents were Joseph and Christine Walker. Joseph Walker owned the now-defunct Laurel Wholesale Grocery. “Mr. Walker,” as his name was passed to me, died rather young, of the effects of a stroke, at the age of 55, in 1943. But his wife, Christine, lived to 92, and I have childhood memories of her watering front yard plants when we arrived for visits. She insisted, rather pointedly, on paying for meals. She enjoyed watching wrestling on T.V., and implored me to never become muscle-bound. (Laziness, not familial duty, led me to oblige.) She told some of the most surreal, fantastical stories I have ever heard, to this day, and she never let facts get in the way. I remember being distinctly aware and amazed, even as a 7- and 8- and 9-year-old child, that “MawMaw,” as I called her, had been born in the nineteenth century. I was so enamored of this that once, in the second grade, following a lesson on U.S. presidents, I was moved to stand from my seat, walk to the teacher’s desk and proclaim to her: “My great-grandmother was born when McKinley was president.” That’s a true story. (I recall the teacher looking up at me, waiting a beat, saying, “Wow,” and then telling me to return to my seat.) But these days, whenever I think of Laurel, and my roots there, and my memories of MawMaw, I inevitably come around to mulling on two things.

One, the petit-fours at M&M Bakery. (Another reason I never became muscle-bound: a subtle, persistent sweet tooth.)

Two, the city’s public parks. Specifically, Gardiner Park.

When I knew her, MawMaw lived near Gardiner Park, and when we would come from Hattiesburg, for day-long visits, I was often told to “go play in the park,” which I did not mind, because there was a long, shallow and minnow-filled creek running through the park, and my imagination could never reach the end of the possibilities that flowed through its water. But years before I came along, MawMaw had lived in a house on North Fourth Avenue that faced Gardiner Park. I am going to guess some of her favorite memories were borne in that house, when her husband was alive, children ran the hallways and the park was just out the front door, across the avenue. Her daughter, Nancy, my grandmother, certainly enjoyed growing up beside the park. Her stories, childhood and otherwise, often mention “the park” with a reverence most Southerners hear when their grandparents discuss “the church.” For my grandmother, “the park” holds that kind of place. And whenever she tells a story in which “the park”—meaning Gardiner Park—figures, she always offers, at the end, as a sort of verbal parenthetical aside, this nugget: “You know, Frederick Law Olmsted designed the park.”

Olmsted—America’s original landscape architect. The guy who designed the grounds at Biltmore, the university campus at Berkeley, the U.S. Capitol grounds and so much more. How did it happen that that guy—or maybe his son—went down to south Mississippi and designed a public park? Well, it’s simple really. Laurel was a town more or less built by Northern timber barons who became Wealthy wealthy—not wealthy, or wealthy wealthy, but Wealthy wealthy—on the region’s pines during the early twentieth century. So when it came time to have a park designed, they had the means and the taste to hire the best there was. It isn’t just my grandmother that tells this story. Most folks connected to Laurel have either heard or told this Olmsted-designed-a-park-in-Laurel story.

Recently, a south Mississippi publication asked if I would be interested in writing something. I pitched a story that would delve into the details of how Olmsted designed a park in Laurel. You know—what he was paid, when he came up with the designs, when construction began, et cetera. The publication liked the idea. I got to work.

What I ended up discovering, in Library of Congress files and elsewhere, is that Olmsted did not design a park in Laurel. Neither did anyone from his firm. Not only this, I discovered the identity of the landscape architects who actually designed Gardiner Park. I put it all in my story, which is below.

I am proud of the reporting on the story but I need to say the whole thing actually makes me kind of sad.

M&M Bakery closed years ago. I’ll never taste one of their petit fours again. And I’ll never again spend time in a park that Frederick Law Olmsted designed in Laurel, Mississippi, either. I sort of want to apologize to my grandmother for that.

One of the most charming and enduring parts of Laurel lore is the story of Frederick Law Olmsted’s landscape architecture firm designing one of the city’s parks.

It goes like this: During the earliest days of the twentieth century, local timber barons hired Olmsted’s Massachusetts-based firm to travel to Laurel to design a first-rate park in the city.

Olmsted, of course, is the most well-known landscape architect, ever. He designed Central Park in New York City, Biltmore in North Carolina and the U.S. Capitol grounds. And nearly everyone with Laurel roots has heard—and most have told—the story about him designing a park in The City Beautiful.

But Pulse has concluded it is not true.

Frederick Law Olmsted never designed a park in Laurel. Neither did anyone from his firm.

Pulse reached this conclusion after an extensive investigation that included scouring the Olmsted firm’s job files, which are housed within the manuscript division of the Library of Congress. The files, of which there are thousands, cover the years 1863 to 1971. Nothing in them suggests Olmsted’s firm ever designed a park in Laurel. This is what led Pulse to dub the Olmsted story false.

After reaching this conclusion, Pulse contacted three Laurel residents with long-term knowledge of the supposed Olmsted connection.

The first asked not to be identified in this article but confirmed the conclusion. “It never happened,” the person said. The second was Evelyn Jefcoat, who has studied landscape architecture for decades. Jefcoat said she always doubted the veracity of the Olmsted story. She added that her late husband, Michael, doubted the story, too. The third person contacted was George Bassi, director of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art. When told that the paper’s reporting indicated no Laurel park was designed by Olmsted’s firm, Bassi replied: “Your reporting is accurate.”

In addition to debunking the Olmsted story, Pulse has identified who designed Gardiner Park, the Laurel park most often cited as a creation of Olmsted firm’s—there is even a sign at the park stating “it is believed to have been designed by the Frederick Law Olmsted firm.”

Before revealing who actually designed Gardiner Park, though, we should attempt to untangle how the erroneous Olmsted-park-in-Laurel story began.

*

It is a story that has been spread for more than four decades—and probably much longer than that.

In 1981, in a story about Laurel locales worthy of being placed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Laurel Leader-Call newspaper stated that Olmsted designed Mason Park. Fifteen years later, the Times-Picayune newspaper in New Orleans, in a piece highlighting how Laurel’s early timber barons “spared no imagination and no expense,” claimed Olmsted firm’s designed Gardiner Park. In 2017, the Associated Press reported that Olmsted designed the city’s park.

As pervasive as the story has been in the media, it has been more so on social media and travel blogs, especially since the “Hometown” explosion eight years ago.

But the story’s real driver has always come via good ole-fashioned word-of-mouth retelling. For people connected to Laurel, relaying the Olmsted connection conveys a sense of civic pride, as well as the refined culture—and deep pockets—of the city’s early residents.

So how did the story come into existence?

Within the Olmsted firm’s job files at the Library of Congress, there are copies of park-related correspondence between several high-profile Laurel residents and the Olmsted firm in 1912 and again in 1941. Both sets of correspondence were initiated by Laurel residents and show that the city was certainly interested in the esteemed firm designing its parks. The firm was open to doing so, too. But for reasons that never come clear, the pairing never happened.

*

In 1912, Laurel resident Wallace Rogers wrote to the Olmsted firm in Massachusetts. Rogers was one of Laurel’s pioneer lumbermen, an Iowa native who came to the city in the 1890s with Eastman-Gardiner. He was also the father of Lauren Rogers, the namesake of Laurel’s art museum.

“Gentlemen,” his letter began, “it is my understanding that you have done considerable work on the Parks in New Orleans. Will you be going down there any time soon? If so, what would you charge to stop over a day or two at Laurel, Miss., to look at a small park proposition?”

Soon after writing that letter, Rogers met with J.F. Dawson, an architect with the Olmsted firm, in New York City. Rogers told Dawson several lumbermen had recently donated 25 acres to Laurel for a park, and they were interested in Olmsted’s firm designing it. Dawson told him the firm could generate a design plan for $500. Rogers said he would discuss it with his associates and get back with the firm. According to the Olmsted firm’s job files at the Library of Congress, Rogers never contacted the firm again.

Almost 30 years later, in August of 1941, Laurel resident T.G. McCallum wrote to the Olmsted firm. McCallum, 68 at the time, was a former Laurel mayor, as well as state Representative and state Senator.

“We are planning to make a public garden on a tract of land owned by the city for park purposes,” McCallum’s letter began. “The terrain lends itself admirably to landscaping.”

McCallum explained that the park would be named William Mason Gardens, in honor of “one of our leading citizens.” Mason, who had died the previous year, started Masonite Corporation.

Three days after receiving McCallum’s letter, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. dictated a response, saying the project “seems like an interesting and attractive one.” He explained he had business in New Orleans soon—the Olmsted firm designed Audubon Park—and could come through Laurel to discuss the matter with the park's trustees. After not hearing from McCallum for two months, Olmsted wrote back in October 1941.

“If you want me to try to arrange for such a visit,” Olmsted wrote, “I would suggest that you let me know as promptly as possible.”

McCallum responded that he was dealing with a “serious illness.” “As soon as some definite conclusion is reached in the matter,” he added, “you will be advised.”

According to the Olmsted firm’s job files at the Library of Congress, Olmsted never heard from McCallum again.

It seems plausible that word of these two efforts to hire Olmsted’s firm began spreading at some point in Laurel. And it is such a good story, it spread for decades, with the most important part—the fact that the firm was never actually hired—eventually being left out altogether.

The story eventually became so accepted that in 2017, when William Mason’s Laurel home, “Greenbrier,” was considered for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, the 50-page nomination form presented it as fact. The form, which listed and described the home’s historical significance, included this paragraph:

The landscape and design came from the Frederick Law Olmsted Group out of New York, the same group that designed Gardiner Park in Laurel. However, the extent of the original Olmsted design that survives is not clear and may be the subject of further study.

There are two problems with that paragraph. One, the Olmsted firm was never based “out of New York City.” The firm came together in the early 1880s in Brookline, Massachusetts, and stayed there until 1979, when, according to the Olmsted Network, “the property, structures and collections became part of the National Park Service as Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.” Two, as previously established, the Olmsted firm did not design Gardiner Park.

It should be noted, too, that the Olmsted firm’s job files at the Library of Congress have no record that suggests the firm ever designed anything at “Greenbrier.”

*

This brings us back to the question: If the Olmsted firm did not design parks in Laurel, who did?

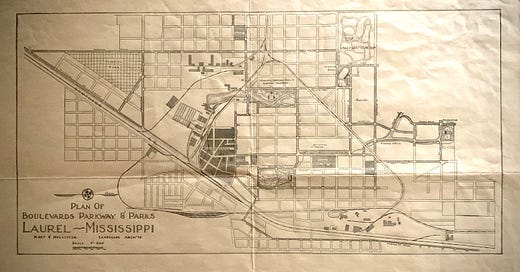

In pursuit of the answer, Pulse discovered that there is a document titled, “Plan of Boulevard Parkways & Parks—Laurel, Mississippi,” at the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art. The faded, one-page document, rectangular in shape, contains a sketched rendering of Laurel’s neighborhoods and parks. The document is not dated but Bassi said he believes it is “from around 1925.” It may be the city’s original planning design, and the bottom left corner of the document shows it to be the creation of, “Root & Hollister—landscape arch’ts.”

Root & Hollister was a rather short-lived landscape architecture firm founded in Chicago, in the early 1920s, by Ralph Rodney Root and Noble Hollister.

Root was a 1910 graduate of Cornell University who then received a master’s at Harvard University, where, coincidentally, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was helping develop a landscape architecture program. Root then led the department of landscape gardening at the University of Illinois. Hollister appears to have been one of his students. A Kansas City native, Hollister graduated from the University of Illinois in 1915 with a degree in landscape architecture and city planning.

Soon thereafter, Root and Hollister created their firm. Root & Hollister appears to have not survived the Great Depression, it was quite active during the 1920s, designing what were described as “show place estates for Chicago millionaires” on the city’s North Shore. If Bassi’s “around 1925” date is correct, the firm created a layout design for Laurel during those years.

But Root & Hollister did not design Gardiner Park itself. That distinction belongs to a landscape architecture firm from Atlanta called Cooke & Swope.

E. Burton Cooke and Harold Brown Swope founded the firm in 1912. Cooke was a Canadian who graduated from the University of Alabama and then worked at the Biltmore gardens for six years. Swope was a West Virginia native who graduated from the University of the South in Tennessee and then studied at the Olmsted firm before also going to work at Biltmore. Soon thereafter, in the fall of 1912, they opened their firm. Contemporary newspapers described it as “the first office to be opened in the south for the practice of landscape architecture.”

According to an article in the March 6, 1913, edition of the Jackson Daily News, the firm had recently “completed plans for the beautifying [sic] of the 20-acre park donated to the city by Eastman-Gardiner & Co.” The article states that the park commission had “formally adopted” the firm’s plan, and it would “be the guide for all proposed work there.”

The Daily News article noted that it would cost $8,000-plus to implement Cooke & Swope’s plan at Gardiner Park. Among other things, the plan called for an athletic field to be built at the corner of Seventh Street and Fourth Avenue. That athletic field, of course, still stands.

Glad I could be of help.