41. A Mississippi historical marker will be placed near the site of Ellisville lynching.

Before daybreak on June 16, 1919, a young white woman named Ruth Meeks arrived at her home in Ellisville and allegedly told her father she had been raped by a black man. Meeks worked at the Pinehurst Hotel1 in Laurel, eight miles north of Ellisville. According to the story told to authorities, she rode a train home the previous evening and at about 10:30 p.m., after getting off, a black man accosted her at gunpoint, causing her to scream. He then raped her near a railroad trestle. Meeks said when the man threatened to kill her, she talked him out of it, and, after several hours, he left wearing her “coat suit”2 as a disguise.3 At about 5 a.m., Meeks’ father told the town marshal his daughter had been raped by a black man.4

Why John Hartfield, a lumber laborer, became the suspect has never been clear, but by noon an armed posse was after him. When a deputy found Meeks’ coat at his home, in Greene County,5 authorities felt it proved guilt. Hartfield was not there, though. When authorities arrived at his house, he was at a neighbor’s, looking to borrow ingredients for homemade ice cream.6 Learning of the situation, he fled. The subsequent search involved thousands of men, four packs of bloodhounds,7 passed through three counties and lasted 10 days.

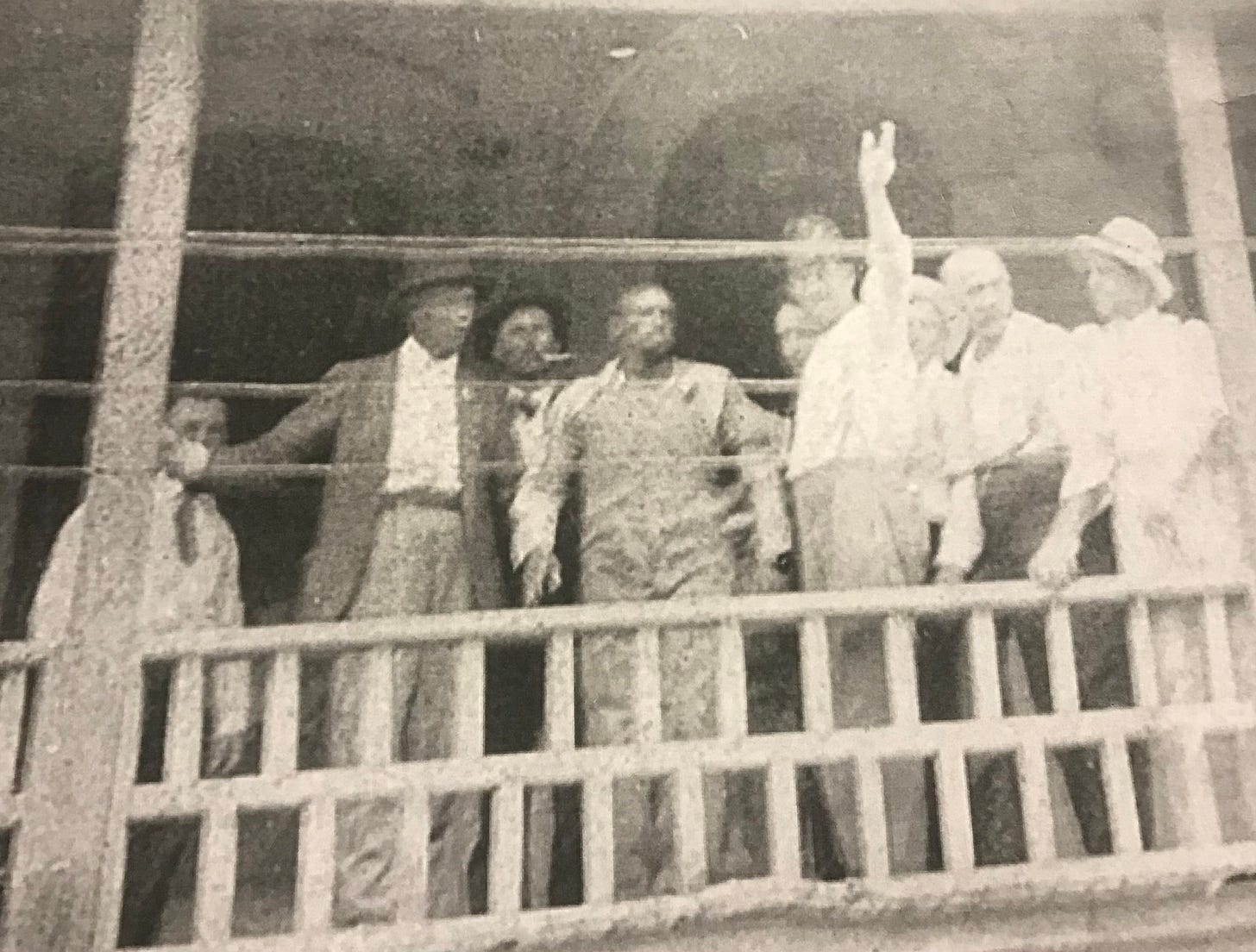

Hartfield was apprehended 20 or so miles northwest of Ellisville, driven back to town and taken to a doctor’s office, where he was treated for a gunshot wound.8 At some point Ruth Meeks came and said the right man had been captured.9 Newspapers quoted Hartfield as saying, “You have the right man.”10 He was then taken outside and, from a second-floor balcony, presented to a crowd gathered on the street below. (A photograph of this moment can be seen above.)

What happened next has never been brought to reckoning.

A group of Ellisville residents formed a committee to arrange a lynching.11 The plan was no secret. The lead headline in the Jackson Daily News on June 26, 1919, announced: “John Hartfield Will Be Lynched By Ellisville Mob At 5 O’Clock This Afternoon.” Roads into town were soon clogged with traffic and businesses within a 50-mile radius closed so employees could attend.12 One report claimed 15,000 people13 made their way to the town of 1,500 residents. Some Jones County elected officials were involved—the chancery clerk had personally driven Hartfield to Ellisville14 and the district attorney,15 along with a future state Supreme Court justice,16 addressed the crowd.

Meanwhile, the NAACP sent a telegram to Gov. Theodore Bilbo, asking him to do something to stop the lynching.17 Bilbo, a repugnant racist, declined.

“I am powerless to prevent it…” the governor said. “As the public is well aware this man-hunt has been in progress since June 15. Thousands have joined in it, excitement is at a fever heat, and any attempt to frustrate a lynching would unquestionably result in hundreds being killed.”18

Accounts vary as to what transpired between a noose being placed around Hartfield’s neck and him arriving at a sweet gum tree. One newspaper account said his “throat was cut and before he was pulled to the top of the tree he was evidently dead.”19 Another said “dozens of men literally jumped on Hartfield, and stamped him to death with their feet.”20 Most accounts agreed that after Hartfield was hanged from the tree, dozens of pistols were fired at him, and he eventually fell. Pieces of his body were cut off for souvenirs.21 What remained was placed atop a collection of pines and crossties that a group of “prominent men”22 had gathered. “[A]n hour later,” the Jackson Daily News reported, “there was only a pile of ashes.”23

Soon thereafter, as with so many unpleasant Mississippi truths, a sort of silence, like unchecked kudzu along a rural roadside, crept over the events of that day. The result has been that for more than a century, no one, from local and state officials to casual citizens to random passersby, has ever had to confront one of the ugliest events in the history of not only Ellisville and Jones County, but Mississippi as a whole.

That will change this summer when, because of a local woman’s efforts, a historical marker detailing Hartfield’s lynching will be placed in Ellisville.

It will be placed along Highway 11. Afterward, anyone who travels that road—right through the heart of town—will pass these words: “The lynching was announced in advance by newspapers, and thousands of spectators watched as Hartfield was hanged from a sweet gum tree and his body riddled with bullets. After being taken down, parts of his body and postcards of the killing were sold as souvenirs and the remains burned.”24

A Jones County native named Marian Allen is responsible for the marker’s creation. Like so many others, the 56-year-old Laurel resident grew up having never heard of Hartfield’s public murder. She first learned about it last year, when an Ellisville man gave her copies of a series of infamous photographs taken during the lynching. In 2020, Allen had founded Laurel-Jones County Black History Museum and Arts, which she uses to share the history of local African Americans, and the man, who discovered the photographs while helping demolish an old Ellisville building, thought she could use the photographs in her exhibits.

Disturbed by the black-and-white images—one showed Hartfield’s body hanging from a tree limb, another showed smoke billowing from a blurry pile of wood—Allen sought out more information. Eventually, she was moved to pursue a marker in Hartfield’s honor because, she said, “people need to be able to see history.” She submitted an application for a state historical marker to the Mississippi Department of Archives & History last fall. In January, she received an email from MDAH notifying her that the application—after being reviewed by a committee that verified the truth of the lynching and its historical significance—had been approved. The marker, currently being constructed in Ohio, will be delivered in coming weeks.

“I don’t want history hidden anymore,” Allen said of why she pursued a marker. “Just acknowledging what happened and not sweeping it under the rug anymore—I see it as part of a healing process.”

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, approximately 4,075 African Americans were lynched in Southern states between 1877 and 1950. The majority of those—654—occurred in Mississippi. Hartfield died during what historians call the “Red Summer,” the period between April and November of 1919, when roughly 52 African Americans were lynched in the U.S. It was “the worst spate…lynchings in American history,” author Cameron McWhirter wrote in “Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America.”

The elements of Hartfield’s murder included three of the most common characteristics of racially-motivated lynchings. One, a crowd of whites committed it in public, the purpose being to terrorize African Americans. “Lynching was terrorism, and as such it was one of the white South’s most effective weapons of repression,” historian Howard Smead has written.25 Two, the people responsible were never prosecuted. Three, the victim had been accused of a violent crime against a white person.

Also, like in so many cases of lynching, there is evidence that suggests Hartfield may have been targeted for reasons other than an alleged rape.

In 2015, journalist Dan Barry wrote a piece26 for The New York Times about accompanying a 107-year-old Black woman named Mamie Lang Kirkland on her first visit to Ellisville in 100 years. Kirkland said her family had fled the town, in 1915, amid rumors that white men were looking to lynch her father, Edward Lang, as well as her father’s friend, John Hartfield. Hartfield left town, too, she said, only to return, four years later, in 1919.

Why did he go back?

According to Kirkland, to be with his white girlfriend.

Barry’s piece never directly states that Hartfield’s consensual relationship with a white woman led to his lynching. It also never mentions Ruth Meeks. Nonetheless, as someone who has sought out information regarding Hartfield’s murder for years, Kirkland’s memories offer potential explanations for several parts of the Hartfield story that have always seemed curious: Why did no one in the neighborhood come to check after Meeks screamed? Why would a man who had just raped a woman think wearing her coat home—in Mississippi, in June—would make for a good disguise? Why, after returning home, would he begin, of all things, making ice cream? And why was Hartfield, who lived 50 miles from Ellisville, the suspect in the first place?

A day or two before he was captured, Hartfield surfaced in Summerland, in northern Jones County.27 While there, he approached an African-American brakeman working on a log train and asked him for help. A story from the June 25, 1919, edition of the Hattiesburg American, stated: “He told the brakeman that he carried the girl’s suitcase from the street car to her home and denied that he assaulted her.”

I suppose it is human nature for that sentence to make me begin to wonder, especially when considering Kirkland’s memories. To wonder if Meeks rode the train home from Laurel to Ellisville that evening. To wonder if a scream sounded along Hill Street at all. To wonder if Meek’s coat was in Hartfield’s home for reasons other than him wearing it there. To wonder if authorities were told Hartfield committed a rape because someone learned a truth that was, in Jim Crow-era Mississippi, unacceptable.

To mostly wonder if Hartfield was admitting to something other than what his captors had accused him of when he said, “You have the right man.”

Seven years before Hartfield’s murder, a crowd converged on the grounds of the Ellisville courthouse to watch a Confederate monument be unveiled.28 It still stands today, topped by an armed Confederate soldier. One side of the monument reads, “Lest We Forget.” The other reads, “The Principles For Which They Fought Live Eternally.” Chief among those principles, of course, was white supremacy, and that principle is what allowed white men to murder Hartfield—and thousands of other African Americans—in broad daylight with impunity.

I live in Ellisville, and that monument should have been removed from the courthouse lawn years ago. It will be eventually. I am sure of that. Until then, downtown Ellisville will be home to two reminders of history standing less than a half-mile apart—one a monument that inexplicably honors an ideology of hate, the other a historical marker that memorializes a man murdered in public by that hate.

The unveiling ceremony for Hartfield’s marker will be at 11 a.m. on June 17, during a local Juneteenth Festival. Allen did not describe the ceremony as an “unveiling,” though. She described it as a “service,” one that will include a minister delivering a eulogy for Hartfield.

Historical markers, though approved by MDAH, are paid for by private sponsors. Allen is paying for the $2,500 marker. Anyone wishing to make a donation, can contact her at 601-323-9418 or ma4099771@gmail.com.

The entire text of the Hartfield marker will read:

Lynching Of John Hartfield

On June 26, 1919, John Hartfield, an African American, was lynched in Ellisville allegedly for raping his White girlfriend. After being apprehended by the county sheriff, he was turned over to a mob. The lynching was announced in advance by newspapers, and thousands of spectators watched as Hartfield was hanged from a sweet gum tree and his body riddled with bullets. After being taken down, parts of his body and postcards of the killing were sold as souvenirs and the remains burned.

“Negro Brute Attacks White Girl,” Jones County News, June 19, 1919.

Ibid.

The Hattiesburg American, in a story from either the June 18 or June 19 edition, in 1919, described the coat as a “disguise” used by Hartfield.

“Negro Brute Attacks White Girl,” Jones County News, June 19, 1919.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Hattiesburg American, June 20, 1919.

“Negro Rapist Caught,” Jones County News, June 26, 1919.

“The Hartfield Lynching,” Jones County News, July 3, 1919.

“John Hartfield, Negro Rapist, Pays Penalty For Atrocious Crime,” The Daily Herald, June 27, 1919.

“John Hartfield Will Be Lynched By Ellisville Mob At 5 O’Clock This Afternoon,” Jackson Daily News, June 26, 1919.

Ibid.

“Hartfield Is Lynched At Scene Of His Crime,” Jackson Daily News, June 27, 1919.

“Negro Rapist Caught,” Jones County News, June 26, 1919.

Hilton Butler, “Lynch Law In Action,” The New Republic, July 22, 1931.

“Negro Rapist Caught,” Jones County News, June 26, 1919.

Cameron McWhirter, Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America.

“John Hartfield Will Be Lynched By Ellisville Mob At 5 O’Clock This Afternoon,” Jackson Daily News, June 26, 1919.

“Negro Hartfield Lynched,” Hattiesburg American, June 26, 1919.

“The Hartfield Lynching,” Jones County News, July 3, 1919.

Butler, “Lynching Law In Action,” The New Republic.

“John Hartfield, Negro Rapist, Pays Penalty For Atrocious Crime,” The Daily Herald, June 27, 1919.

“Hartfield Is Lynched At Scene Of His Crime,” Jackson Daily News, June 27, 1919.

The marker’s text was offered by the Mississippi Department of Archives & History.

Howard Smead, Blood Justice: The Lynching of Mack Charles Parker.

Dan Barry, “Horror Drove Her From South. 100 Years Later, She Returned,” The New York Times, Sept. 19, 2015.

Hattiesburg American, June 25, 1919.

For information on the Confederate monument in Ellisville, refer to National Register of Historic Places application.